China’s Communist Party has a history of purging and then welcoming back senior officials. Deng Xiaoping was purged three times before leading the country out of Maoism in the late 1970s. Some cadres are welcomed back years after their death. Jack Ma, Alibaba’s founder, endured the modern version of a purge in 2020. The initial public offering (ipo) of his fintech company, Ant Group, was cancelled. Alibaba was probed shortly thereafter and handed a record fine. Mr Ma withdrew from public life.

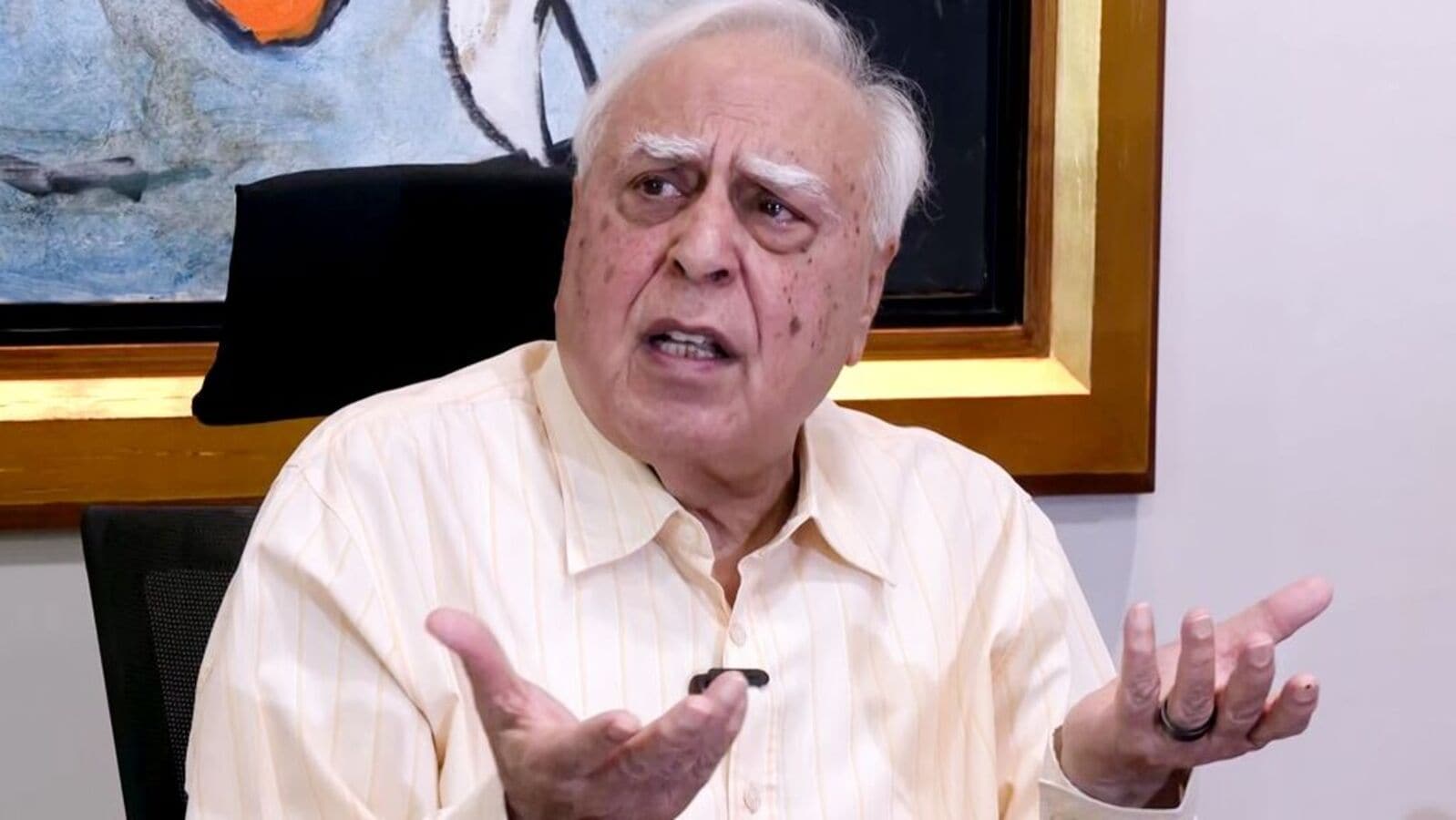

Now, however, he seems to be welcome once again. On February 17th Mr Ma along with a handful of other entrepreneurs met at a symposium in Beijing with Xi Jinping, China’s supreme leader. Many see this as Mr Ma’s rescue from the wilderness—and a sign that, after a prolonged crackdown, private-sector tech is back in favour.

It certainly has the makings of the most lucrative rehabilitation of all time. On February 14th Alibaba’s share price rose by 6.2% on rumours of the symposium, adding roughly $18bn to its market value. Those of Tencent and Xiaomi, two other large tech firms, rose by 7%. That comes on top of a rally in recent weeks. Shares in Hang Seng Tech, an index of the 30 largest technology companies listed in Hong Kong, have risen by 23% in the past month; those in Alibaba have surged by over 50%. Is a revival in private-sector sentiment at last under way?

In large part the rally has been prompted by DeepSeek, a Chinese artificial-intelligence (AI) firm that has managed to keep up with Silicon Valley even without an ample supply of American chips. Analysts at Bank of America have compared it to Alibaba’s IPO in New York in 2014, which caused a boom in innovation at consumer-internet firms. DeepSeek, they think, could have a similar effect.

Many companies are already adopting DeepSeek’s model. Tencent, an internet and gaming group, is said to be testing it in Weixin, an application that offers messaging, payments, shopping and entertainment services, in the hope of creating an ai “super app”. AI could also boost demand for cloud-services providers, such as Alibaba, Huawei and Tencent. They, in turn, will have to invest more in building server farms, benefiting the suppliers of AI data-centre components. Alibaba is also reportedly working with Apple, an American tech giant, to inject AI capabilities into the iPhones sold in China.

Yet despite all that, wider sentiment has still been weak. The Business Confidence Index, a monthly survey of more than 300 senior executives at corporations across China, showed slight improvements in January. But several important components of the index, such as the outlook for corporate financing and inventory, are still contracting. Moreover, that same month the compilers of an index at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing concluded that “fairly significant levels of instability continue to inhibit China’s business sphere”.

That helps explain Mr Xi’s appearance at the symposium. According to reports of the meeting, he underlined the importance of the private sector for China’s economy and acknowledged some of the problems facing it. Mr Xi’s time in power has been an experiment in how best to guide entrepreneurs while also limiting their influence over policymaking and society. Senior officials have never managed to find a comfortable balance. Between 2013 and 2019 the biggest companies dominated investment as well as many areas of economic growth, putting officials in the passenger seat of development.

The crackdown in 2020 reversed things sharply, wiping around $2trn off the value of China’s stockmarkets in the process. More recently the party has sought to guide entrepreneurs without extinguishing their innovation. The result has been an intentional blurring of the lines between private and state enterprise. This works for some companies such as Huawei, a telecoms giant; Cambricon, a chip designer; and iFlyTech, an AI company. But the result is often a murky hybrid. Academics have labelled it “party-state capitalism”.

Given all this, the love-in can only do so much to restore sentiment. Chinese private-sector elites want more than symposiums. Big problems afflict their companies. For example: when, asks a Hong Kong-based venture capitalist, might regulators loosen their control of IPOs? Since the crackdown, approval processes for listing overseas have been introduced. Startups such as Shein, a fast-fashion firm, have been forced to seek informal approval from Chinese regulators on national-security grounds. The securities watchdog has taken it upon itself to manage the listing expectations for some companies, reportedly halting the IPO in Hong Kong of a tea-and-ice-cream chain last year because valuations were too low.

A snarl-up of other problems shows no sign of abating. Rather like many tech firms, the financial system has also become a public-private hybrid. China’s venture-capital and private-equity industries have been permeated by the state. For many startups state capital, with its irreconcilably different goals from the private version, has become the main form of funding. Businessmen once laughed off the influence of Communist Party cells in private firms, which have been around for ages. Yet over the past five years these cells have amassed much more power. There are few signs that this trend will reverse.

In some quarters the return of Mr Ma has been portrayed as a big win for the private sector—or even a concession to it. But it might also be seen as a victory lap for Mr Xi. Over the past five years China’s entrepreneurs have become much more subservient to the Communist Party. They must play by Mr Xi’s rules or face the consequences. The symposium is a confirmation that China’s once-mighty entrepreneurs have fallen into line.

© 2025, The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved. From The Economist, published under licence. The original content can be found on www.economist.com

Leave a Reply